The Birmingham Qur’an fragments: Are they really that old?!

In July 2015, when a PhD researcher looked more closely at some fragments inside a more recent copy of the Holy Book (Qur’an), it was decided to carry out a radiocarbon dating test.

The tests were carried out by the Oxford University Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit. These tests provide a range of dates. Hence, they showed that the parchment (sheep or goat skin) was from the period between 568 and 645 CE.

Based on these results, researchers concluded that the manuscript was among the earliest written textual evidence of the Islamic Holy Book known to survive.

These pages of the Qur’an had remained unrecognised in the Birmingham University Library for almost a century. The manuscript is part of the University’s Mingana Collection of more than 3,000 Middle Eastern documents gathered in the 1920s by Alphonse Mingana, a Chaldean priest born near Mosul in modern-day Iraq. He was sponsored to take collecting trips to the Middle East by Edward Cadbury, who was part of the chocolate-making dynasty.

These four pages of the Qur’an, in early Arabic script, sparked fierce debate among scholars.

The assertion that the document, kept at Birmingham University, is part of one of the world’s oldest copies of the Qur’an is strongly disputed by many scholars in the field of codicology and palaeography, who point out that the science of carbon dating is contradicted by other evidence.

Among these scholars is Qasim al-Samarrai, Professor Emeritus of Palaeography and Codicology (Leiden – Holland), who, in relation to this subject says:

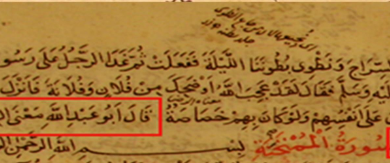

“The fragments of the Qur’an folios that were found at Birmingham are not at all what they are claimed to be. They in fact belong to the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 3rd century AH (after Hijrah), if not later. All the features in them: the script, dotting, using golden and red ink as well as the separation of verses (Ayat) and chapters (Suwar)…etc., indicate that they might have been written on parchments older than the script. Therefore, they are not as early as is thought. Surprisingly enough, Berlin and Tubingen claim the same with their own fragments.”

Furthermore, Professor Al-Samarrai highlights five important facts in this respect:

1) Fact one: We possess no dated Qur’an copy belonging to the first three centuries of Hijrah.

2) Fact two: We possess almost 250 thousand – if not more – fragments and various leaves of the Qur’an, written on either parchments or papyrus, scattered all over the world, but not a single one bears a date. Thus, from this platform, I strongly challenge any scholar, working with the Qur’an palaeography, and in particular those “revisionists”, to produce one dated folio belonging to the span of time that lies between the year 40 AH (660 CE) and 300 AH (912 CE).

3) Fact three: C14 test is doubtful due to the pollution in the sphere and the craft of manufacturing parchments in the East.

4) Fact four: The text of the Qur’an depended from the beginning of the revelation on memory, not writing; as one orientalist says: “The transmission of the Qur’an after the death of Muhammad was essentially static, rather than organic. There was a single text, and nothing significant, not even allegedly abrogated material could be taken out nor could anything be put in.” Or, as one of the contemporary revisionists likes to put it: ‘’The Qur’an was revealed in actual language, not in scriptural form. The script available at the time of revelation was highly defective(sic), so that it constituted not more than an aid for those who knew the text by heart already… being well aware that the oral tradition is the more important and valid one.’’

The oral tradition of the Qur’an is a phenomenon very unique to Islam, in memorising the whole Book (Qur’an); though we know that some Buddhist monks recite some of their holy text in their sermons. There were, and still are, many millions of people who have memorised the Qur’an, and millions of these have learnt the Qur’an via a direct transmission, starting from the Prophet himself. They are enumerated with the chain of transmitters (isnads) in the reciters’ (qurra’) biographical sources; published or unpublished. It is, therefore, difficult to believe that, in some parts of the world, long religious texts are still memorised and transmitted from generation to generation, as it is in Islam.

5) Fact five: In spite of all the information we gleaned from many sources at our disposal in connection with Uthmans’ copies, no copy belonging to Uthman time ever survived; though many existing copies have been attributed falsely to him or to any individual contemporary with him.

Professional background of Professor Qasim al-Samarrai:

- 1958: BA (Hon) in Arabic Literature and History from the Faculty of Education, University of Baghdad.

- 1965: PhD in comparative mysticism (Ascension in Mystical Writings) from the University of Cambridge, UK under the supervision of Prof A.J. Arbery. At the same time, he held the post of lecturer at the Department of Oriental Studies, Cambridge University, UK.

- 1966 – 1969: Assistant professor at the Faculty of Shari’ah and at the Faculty of Arts – Department of Philosophy of the University of Baghdad, as well as at al-Mustansiriyya University in Baghdad.

- 1970 – 1976: Held the post of lecturer of Arabic literature and Islamic History at the Department of Arabic & Islamic Studies of the University of Leiden, the Netherlands.

- 1977 – 1980: Affiliated Professor to the Department of Islamic Studies, the Faculty of Theology of the University of Leiden, the Netherlands.

- 1980 – 1981: Held the post of Professor of Islamic Philosophy at the Faculty of Philosophy, University of Qâr Yunus, Banghâzi, Libya.

- 1981 – 1983: Held the post of Professor of Islamic Civilisation and Islamic Education in the Faculty of Arabic Studies and at the Research Centre, both of the University of Muhammad bin Saud in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- 1983 – 1986: Held the post of Professor of Arabic & Islamic Palaeography and Codicology in the Department of Libraries & Information at the Faculty of Social Studies of the University of Muhammed bin Saud in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- 1987- 2003: Affiliated Professor to the Department of Studies of Comparative Religions, the Faculty of Theology of the University of Leiden, the Netherlands.

Professor Al-Samarrai has published more than 60 books, the last of which is a critical edition of Al-Badr al-Safir by Al-Udfawi, in 3 vols. (together with Tariq Tatami); published by Al-Rabita al-Muhammadiyya lil-‘Ulama’, Rabat 2015.

He has supervised a few MA and PhD dissertations in Palaeography and Codicology in the Department of Libraries & Information at the Faculty of Social Studies of the University of Muhammed bin Saud in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Also, he has participated extensively in national and international congresses, as well as many training courses on handling and cataloguing Islamic Manuscripts, organised by Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation (such as the courses held in Istanbul, London, Kuala Lampur, Cairo, Casablanca and Rabat), as well as in Jum’a al- Majid Center in Dubai, King Faisal Centre for Islamic Studies in Riyadh, the King Fahd National Library in Riyadh, the Department of Libraries of King Saud University in Riyadh and King Abdul Aziz Library in Riyadh.

To see the images of the Birmingham Qur’an fragment and the public viewing of it held in October 2015 click – HERE

Video of the lecture (starts on the 12th minute of the video) held at the Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation in London on Monday 23rd November 2015:

so do you believe that quran was compiled 300 yrs later after prophet (saw) passed away

No